Here are they are

The one on the right is an ever-popular 992, the one on the left something a little more special, a 990.

First the 992:

This was one of the most popular 16 size 21 jewel Railroad watches. It was made from 1903 through the mid 1930s(when it was replaced by the 992E and later the all-new 992B). There were over 400,000 992s made.

This one's not in the best of shape. The case is rough and is much too late for the watch. Also, besides the obvious missing second hand, the balance staff and mainspring are broken.

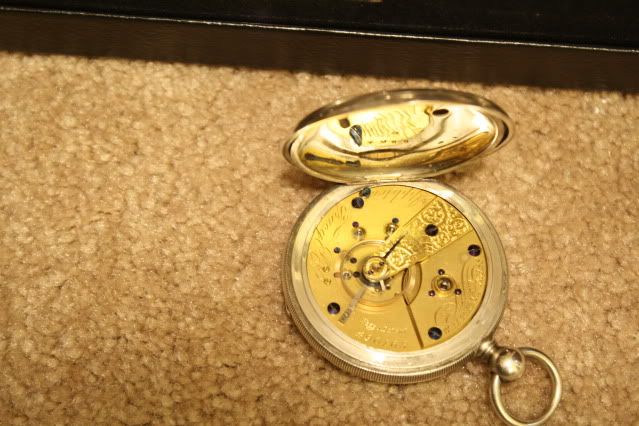

Now, the 990:

The 990 was an upgraded version of the 992. Where the 992 has a gold center wheel, the 990 has gold train. The damaskeen is much nicer on the 990, and extends to the pallet bridge. The regulator spring has the edges nicely rounded and polished.

Also, all 990s were fitted with a double roller escapement, where the 992 was initially fitted with a single roller(although later runs were fitted with a DR-the 990 was phased out about the same time the 992 went to DR).

Even more interesting, the 990 was made in much smaller numbers, with total production only around 16,000.

This one is cased in an unoriginal but very nice sterling case, and runs great.